The New York Review of Books, and Salmagundi, to which she contributes a regular film column. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in biography, a Cullman Fellowship at the New York Public Library, a Leon Levy Fellowship in biography, and the Roger Shattuck Prize for Criticism. Her first book, A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction (Oxford University Press, 2011), was a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

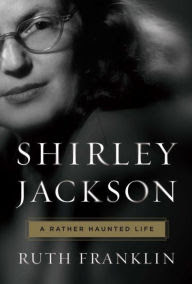

The New York Review of Books, and Salmagundi, to which she contributes a regular film column. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in biography, a Cullman Fellowship at the New York Public Library, a Leon Levy Fellowship in biography, and the Roger Shattuck Prize for Criticism. Her first book, A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction (Oxford University Press, 2011), was a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.Franklin applied the “Page 99 Test” to her new book, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, and reported the following:

Much of page 99 is occupied by a large photograph of Stanley Edgar Hyman, Shirley Jackson’s future husband, taken during his college years and inscribed to her, “Love, look with favor…” Jackson first caught Hyman’s attention when he read her short story “Janice” in a college literary magazine—he decided on the spot that he wanted to marry her. Despite their intellectual affinities, in many ways Jackson and Hyman were perfect opposites. The daughter of a socialite and a businessman, Jackson was raised as a Christian Scientist in the tony suburb of Burlingame, California, and knew as a child that she wanted to become a fiction writer. Hyman, on the other hand, had a traditional Jewish upbringing in Brooklyn (though he was an atheist and a Communist by the time Jackson met him) and found his calling as a critic almost as early. He saw Jackson as his ideal subject, and saw himself as the cool-headed intellectual who would help her realize her full creative powers and then explain her genius to the world.Visit Ruth Franklin's website.

The relationship was tumultuous from the start. The differences in their backgrounds couldn’t have helped, but the real problem was Hyman’s infidelity, which would persist throughout their nearly twenty-five-year marriage. Why Jackson stayed with Hyman—and there is considerable evidence that she may have considered divorce—is one of the enduring questions of her life story. In addition to being unfaithful, he belittled her and put pressure on her to constantly produce the women’s magazine stories that supported their family. (Jackson was the breadwinner during most of their marriage.) Yet he also was her greatest champion and cheerleader, writing copious notes on all her drafts and constantly exhorting her to improve.

After Jackson’s sudden death from a heart attack at age forty-eight, just a few days before their twenty-fifth anniversary, a grief-stricken (and perhaps guilt-stricken) Hyman devoted himself to promoting her reputation. “I think that the future will find her powerful visions of suffering and inhumanity increasingly significant and meaningful, and that Shirley Jackson’s work is among that small body of literature produced in our time that seems apt to survive,” he wrote in the introduction to The Magic of Shirley Jackson, an anthology of her work that he compiled. By now, it seems safe to say that he was correct.

--Marshal Zeringue